What's the most common identifier in Go's stdlib?

This is the blog post form for the latest justforfunc episode of the same title. And the code for the program can be found here, in the justforfunc repository.

Problem statement

Imagine you’ve been given this program below and you want to extract all of the identifiers in it.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Println("Hello, world")

}We should obtain a list containing main, fmt, and Println.

How could we do this? We could use grep with a regular

expression, but … that would be a pretty complicated one!

What is an identifier anyway?

In order to answer this we need to go a bit into language theory. Just a bit, do not worry.

Programming languages are defined, among other things, by a series of rules of what is a valid program. These rules look something like:

IfStmt = "if" [ SimpleStmt ";" ] Expression Block [ "else" ( IfStmt | Block ) ] .This rule tells us what an if statement looks like in Go. The "if", ";",

and "else" pieces are keywords that help us figure out the structure of the

program, while Expression Block, SimpleStmt, etc are other rules.

The set of these rules is called a language grammar. You can find all of them in the Go language specification.

These rules are not defined on the characters of the program,

instead they’re defined on tokens.

These tokens are atoms like if or else, but also slightly more complex

kinds such as integers 42, floats 4.2, strings "hello", or … identifiers

like main.

But how do we know that main is an identifier and not a number?

Well, there’s also rules for this. If you read the

identifiers section of the

Go specification, you’ll find this rule:

identifier = letter { letter | unicode_digit } .In this rule, letter and unicode_digit do not represent tokens; they’re

classes of characters. So given all of these rules, it is pretty straight-forward

to write a program that goes character by character and each time it detects

a group of them that matches a rule it just “emits” a token.

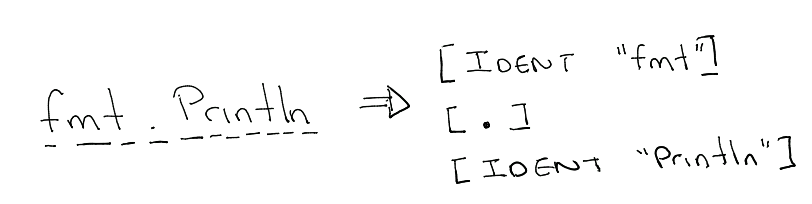

So if we start with: fmt.Println it would generate the tokens: fmt as an

identifier, ., and Println as an identifier. Is this a function call?

Well, at this point we do not know, and we do not care. The only structure

is a sequence letting us in what order things appear.

This kind of program that given a sequence of characters generates a sequence

of tokens is called a scanner. The Go standard library comes with a scanner

for Go programs in go/scanner. The kinds of tokens it generates are defined

in go/token.

Using go/scanner

Ok, so now that we understand what a scanner is. How do we use it?

Reading arguments from the command line

Let’s start with this simple program that simply prints all of the arguments given when executing it. We’ll go from there.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"os"

)

func main() {

if len(os.Args) < 2 {

fmt.Fprintf(os.Stderr, "usage:\n\t%s [files]\n", os.Args[0])

os.Exit(1)

}

for _, arg := range os.Args[1:] {

fmt.Println(arg)

}

}Next we need to scan every one of the files given as arguments. To do this

we will need to create a new scanner.Scanner and initialize it with the

contents of the file.

Printing each token

Before we can call the Init method in scanner.Scanner we will read the

file contents and create a token.FileSet holding a token.File per file

we scan.

Once the scanner has been initialized we can call Scan and print the token

we obtain. Once we reach the end of the file scanned, we will obtain an EOF

(End Of File) token.

fs := token.NewFileSet()

for _, arg := range os.Args[1:] {

b, err := ioutil.ReadFile(arg)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

f := fs.AddFile(arg, fs.Base(), len(b))

var s scanner.Scanner

s.Init(f, b, nil, scanner.ScanComments)

for {

_, tok, lit := s.Scan()

if tok == token.EOF {

break

}

fmt.Println(tok, lit)

}

}Counting tokens

Great, so we’re able to print all tokens, but we need to keep track of how many times we see each identifier, sort them by how many times we saw them, and print the top 5.

In Go, the best way to do so is to use a map where the key will be the identifier, and the value how many times it’s been seen so far.

counts := make(map[string]int)Each time we see an identifier, we need to increment its counter.

for {

_, tok, lit := s.Scan()

if tok == token.EOF {

break

}

if tok == token.IDENT {

counts[lit]++

}

}And at the end, we convert the map into a slice of pairs, which we can sort and print.

type pair struct {

s string

n int

}

pairs := make([]pair, 0, len(counts))

for s, n := range counts {

pairs = append(pairs, pair{s, n})rm -f

}

sort.Slice(pairs, func(i, j int) bool { return pairs[i].n > pairs[j].n })

for i := 0; i < len(pairs) && i < 5; i++ {

fmt.Printf("%6d %s\n", pairs[i].n, pairs[i].s)

}The full source code can be found here, in the justforfunc repository.

So … what’s the most common identifier in the Go standard library?

So let’s simply run the program giving with the contents of github.com/golang/go.

$ go install github.com/campoy/justforfunc/24-ast/scanner

$ scanner ~/go/src/**/*.go

82163 v

46584 err

44681 Args

43371 t

37717 xOk, so the most used identifier is v, talk about short identifiers!

Let’s count only those identifiers that are three characters or longer, by

modifying the code above a bit:

for s, n := range counts {

if len(s) >= 3 {

pairs = append(pairs, pair{s, n})

}

}And run it again:

$ go install github.com/campoy/justforfunc/24-ast/scanner

$ scanner ~/go/src/**/*.go

46584 err

44681 Args

36738 nil

25761 true

21723 AddArgNothing too surprising here, err and nil are present in basically

every single program that does if err != nil. What about Args, though?

That’s a topic for a next episode.

Thanks

If you enjoyed this episode make sure you share it and subscribe to justforfunc! Also, consider sponsoring the series on patreon.