Why are there nil channels in Go?

This blog post is complementary to episode 26 of justforfunc which you can watch right below.

Everybody that has written some Go knows about channels. Most of us also know that the default value for channels is nil. But not many of us know that this nil value is actually useful.

I got this same question on twitter, from a developer learning Go, wondering whether Go nil channels existed just for completeness.

It does makes sense to wonder whether they’re useful, as their behavior seems to indicate otherwise.

Given a nil channel c:

<-creceiving fromcblocks foreverc <- vsending intocblocks foreverclose(c)closingcpanics

But I still insist they are useful. Let me introduce a problem whose solution seems obvious at first, but it is actually not as easy as one might think and actually benefits from nil channels.

Merging channels

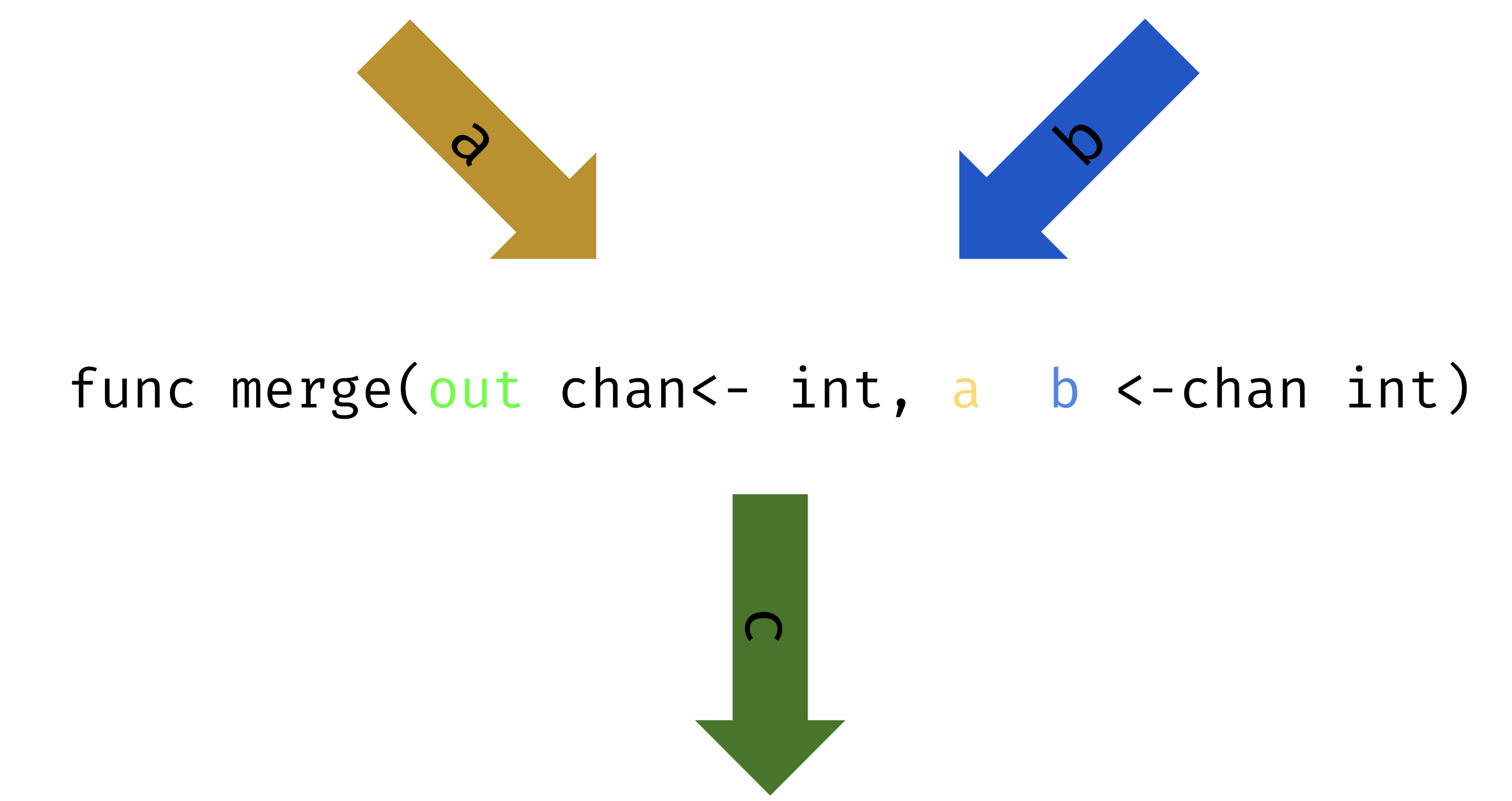

Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to write a function that given

two channels a and b of some type returns one channel c of the same type.

Every element received in a or b will be sent to c, and once both a and

b are closed c will be closed too.

An auxiliary function

Before we start, let’s write a function that will help us test our solution. This function returns a channel that will eventually receive, at random intervals, all of the given values and finish by being closed.

func asChan(vs ...int) <-chan int {

c := make(chan int)

go func() {

for _, v := range vs {

c <- v

time.Sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(1000)) * time.Millisecond)

}

close(c)

}()

return c

}This function creates a channel, starts a new go routine that sends values to the created channel, and finally returns the channel.

This is pretty common pattern when dealing with channels, so make sure you understand how it works before you continue reading.

Let’s get started

Since we don’t really have a preference over a or b we’re going to avoid

creating a preference by choosing on which channel we should range first.

Let’s instead keep the symmetry and use an infinite loop and select over both channels.

func merge(a, b <-chan int) <-chan int {

c := make(chan int)

go func() {

for {

select {

case v := <-a:

c <- v

case v := <-b:

c <- v

}

}

}()

return c

}This looks pretty good, let’s write a quick test and run it.

func main() {

a := asChan(1, 3, 5, 7)

b := asChan(2, 4, 6, 8)

c := merge(a, b)

for v := range c {

fmt.Println(v)

}

}This should print 1 to 8 in some order and end successfully. Let’s see what happens.

> go run main.go

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

0

0

0

0

0

0

0

😱Ok, so clearly this is not good because the program doesn’t ever finish. Once it has printed the values from 1 to 8 it starts printing zeros forever.

Handling closed channels

What happens when we receive from a closed channel? We get the default value

of the type of the channel. In our case, the type is int so the value is 0.

We could check for channels being closed by comparing to zero, but what if one of the values we received was a zero? Instead we can use the “value comma ok” syntax:

v, ok := <- cWhen using this syntax ok is a boolean that will be true for as long the

channel is open. Knowing this we can avoid sending superfluous zeros into

c.

We should also stop iterating at some point … so let’s keep track of when both channels are closed too.

func merge(a, b <-chan int) <-chan int {

c := make(chan int)

go func() {

adone, bdone := false, false

for !adone || !bdone {

select {

case v, ok := <-a:

if !ok {

adone = true

continue

}

c <- v

case v, ok := <-b:

if !ok {

bdone = true

continue

}

c <- v

}

}

}()

return c

}This looks like it might work! Let’s run it.

> go run main.go

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

fatal error: all goroutines are asleep - deadlock!

goroutine 1 [chan receive]:

main.main()

/Users/francesc/src/github.com/campoy/campoy.cat/site/static/code/nilchans/main.go:13 +0x186

exit status 2Ooops, we forgot something. What could that be? Well, we can see that there’s only one go routine running and it’s blocked on line 13. That line is:

for v := range c {Can you see what the problem is? Well, a range statement iterates over all the

values in a channel until the channel is closed. But who is closing the channel?

We forgot! Let’s add a defer statement in our go routine to make sure the channel

is closed eventually.

func merge(a, b <-chan int) <-chan int {

c := make(chan int)

go func() {

defer close(c)

adone, bdone := false, false

for !adone || !bdone {

select {

case v, ok := <-a:

if !ok {

adone = true

continue

}

c <- v

case v, ok := <-b:

if !ok {

bdone = true

continue

}

c <- v

}

}

}()

return c

}Note that the defer statement is inside of the anonymous function called in a

new go routine, rather than inside of merge. Otherwise c would be closed as

soon as we exited merge and sending a value into it would panic.

Let’s run it and see what happens.

> go run main.go

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8This looks great … but is it?

Busy loops

The code we wrote so far is pretty good. It is functionally correct, but if you deployed this in production you might end up running into performance troubles.

In order to show you where the problem is, let’s add a bit of logging.

func merge(a, b <-chan int) <-chan int {

c := make(chan int)

go func() {

defer close(c)

adone, bdone := false, false

for !adone || !bdone {

select {

case v, ok := <-a:

if !ok {

log.Println("a is done")

adone = true

continue

}

c <- v

case v, ok := <-b:

if !ok {

log.Println("b is done")

bdone = true

continue

}

c <- v

}

}

}()

return c

}Let’s run it and see what happens.

> go run main.go

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

a is done

2018/01/14 20:47:22 b is done

... 😱

2018/01/14 20:47:23 b is done

2018/01/14 20:47:23 a is doneUh oh! It seems once a channel is done we keep on iterating non-stop!

It does make sense after all.

As we saw at the beginning reading from a closed channel never blocks.

Therefore the select statement will block as long as both channels are

open until a new element is ready, but once one of them closes we will

iterate and waste CPU.

This is also known as a busy loop, and it’s not good.

Disabling a case in a select statement

In order to avoid the busy loop describe previously we would like to disable

a part of the select statement. Concretely, we’d like to remove

case v, ok := <- a when a is closed and similarly for b.

But how?

As we mentioned at the beginning, receiving from a nil channels blocks forever.

So to disable a case receiving from a channel, we can simply set that channel

to nil!

We can then stop using adone and bdone and instead check for a and b

being nil.

func merge(a, b <-chan int) <-chan int {

c := make(chan int)

go func() {

defer close(c)

for a != nil || b != nil {

select {

case v, ok := <-a:

if !ok {

fmt.Println("a is done")

a = nil

continue

}

c <- v

case v, ok := <-b:

if !ok {

fmt.Println("b is done")

b = nil

continue

}

c <- v

}

}

}()

return c

}Ok, hopefully this will avoid unnecessary loops. Let’s try it.

> go run main.go

2

1

4

3

6

5

8

7

b is done

a is doneThe code for the final solution is on GitHub.

Victory!

This is just one of the many concurrency patterns that can benefit from nil channels. Have you used nil channels to solve some other problems? Share your story! You can get in touch with me on twitter or simply dropping a comment here.

If you enjoyed this episode make sure you share it and subscribe to justforfunc! Also, consider sponsoring the series on patreon.